Top 10 comedy movies......

By rights you should hate Airplane!, simply because its influence stretches to every single woeful parody film made in the last three decades. Without Airplane! there'd be no Epic Movie or Date Movie or Meet the Spartans or Robin Hood: Men in Tights. But, despite all the pain and misery that it's indirectly inflicted on the world, do you hate it? Of course not. That's because Airplane! is untouchably brilliant.

The plot is an irrelevance – if you must know, there's a virus that takes hold of a plane full of passengers – because it's merely a peg to hang hundreds and hundreds of jokes on. The density of gags that writers Jim Abrahams and David and Jerry Zucker manage to squeeze into its 88 minutes is nothing short of breathtaking. They come so thick and fast, and they're delivered with such irresistible deadpan sincerity, that repeated views are a must. And what makes Airplane! all the more incredible is that it refuses to be dulled by familiarity. No matter how many times it gets quoted, or how many of its catchphrases have entered the modern lexicon, Airplane! is still as fresh now as it was on its release. Glorious. Stuart Heritage

9. Monty Python's Life of Brian

Although the Pythons were originally inspired by a title (Jesus Christ: Lust for Glory) to make an irreverent biblical comedy, Life of Brian is not about the son of God. It's about the guy in the next-door manger, born on the same night: Brian Cohen. It was an easy mistake to make; even the three wise men were momentarily fooled. Predictably, the film caused widespread outrage; accusations of blasphemy prevented it from being screened in many countries, while the marketing campaign cheerfully capitalised on the protest, proclaiming the film "so funny it was banned in Norway".

In spite of his obvious lack of divinity, and the fact that he's more interested in women and anti-imperialist politics than religion, Brian (Graham Chapman) is plagued by followers convinced that he's the saviour. The real Jesus is glimpsed at one point delivering his Sermon on the Mount, but Brian is so far back in the crowd that the people around him are wondering what Jesus meant by "blessed are the cheesemakers". Brian fixates on a rebellious young woman called Judith and gets tangled up with the People's Front of Judea (not to be confused with the Judean People's Front). A series of misadventures and misunderstandings lead him to Calvary, where the whole Messiah mix-up reaches its painful, and tuneful, climax.

The film was shot in Monastir, Tunisia, for $4m, with financing from George Harrison's HandMade Films, and each of the Pythons plays at least three roles.Michael Palin played 12, including a Boring Prophet and an ungrateful ex-leper who complains that, by curing him, Jesus has taken away his source of income.

These days, Life of Brian exists less as a film than as a series of endlessly quoted gags floating around in the popular imagination. People who have never even seen it can still chuckle heartily at "What have the Romans ever done for us?", or whistle Always Look on the Bright Side of Life. It's not like the Pythons took the narrative terribly seriously either: at one point, Brian is plucked out of a tight situation by a visiting alien spaceship. This is not necessarily a shortcoming, more a classic Python method of sending up something rather silly that has been taken far too seriously for its own good. Killian Fox

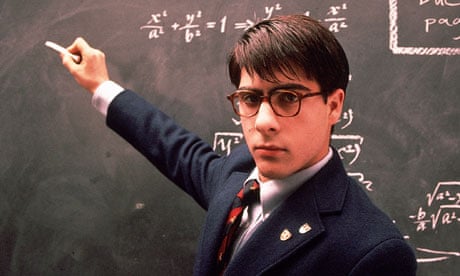

8. Rushmore

Shortly after finishing this, his second feature film, Wes Anderson arranged a private screening for the New Yorker's esteemed former film critic, Pauline Kael. After the lights came up, the 79-year-old turned toward this fresh-faced auteur, 50 years her junior, and said: "I don't know what you've got here, Wes … I genuinely don't know what to make of this movie."

Who can blame her? Even now that we understand exactly what is meant by a Wes Anderson film, Rushmore looks and sounds as rich and strange as ever with its story of unlikely romantic jousting playing out against a privileged East Coast backdrop to the jangling guitars of a "British Invasion" soundtrack (the Kinks, the Who, the Rolling Stones).

In his dazzling screen debut, Jason Schwartzman plays 15-year-old Max Fischer, a pupil at the elite Rushmore academy. The earnest, emphatic Max is president of everything from the debate team to the beekeeping society. When he becomes smitten with a teacher, Miss Cross (Olivia Williams), he resolves to build her an aquarium. But he has a rival in love – the melancholy billionaire Mr Blume, played by Bill Murray.

Max and Blume, essentially the same character at different stages of decay, begin their psychological duel over Miss Cross; and Anderson nudges the humour to the brink of despair, in the style of 70s black comedies like The Heartbreak Kid or Harold and Maude. Max's home is adjacent to a cemetery, and the film is on similarly intimate terms with bleakness. There's Max, in one of the academy's upper windows, aiming his air rifle at a schoolmate in a pitiful echo of Malcolm McDowell in If … And behold his hateful snarl when rebuffed by Miss Cross: "Rushmore was my life," he spits. "Now you are!" Suddenly he sounds like a stalker in the making.

Astonishingly, Anderson keeps us laughing as we wince. Savour the extravagant stage productions by the Max Fischer Players (an amateur Serpico, or a Vietnam epic complete with dynamite), which are not so much am-dram as wham-bam. And relish the gently batty performance which established Bill Murray's reign as an offbeat indie god. Anderson would go on to make more ambitious and extravagant movies, but it is Rushmore, co-written with Owen Wilson, that is truly touched by comic genius. Ryan Gilbey

7. Duck Soup

About 10 months after Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany, Duck Soup opened. Is there any way of reconciling (or separating) these two events? Which moustache was the more dangerous or absurd? In the movie, Groucho played Rufus T Firefly, president of Freedonia, ready to defend the honour of Mrs Teasdale (Margaret Dumont) – if he could find it – by going to war with Sylvania. It is respectable to claim that anti-war films of the early 30s are really important and frightening. But I'm not sure the blithe pro-war stance of Duck Soup hasn't lasted better as a clue to how crazy the 30s were.

McCarey didn't actually want to make Duck Soup. He only renewed his contract at Paramount when told the Marx brothers had quit. But then they sneaked back and he was trapped. "The most surprising thing," he said later, "was that I succeeded in not going crazy, for I really did not want to work with them: they were completely mad."

Groucho is in charge of the movie and he talks all over it, like a dog peeing to mark out territory. I am told that otherwise solemn children can be reduced to writhing masses of delirium by this stuff. It also has the mirror sequence. Of course, in hindsight, a good historian would have known – any country that could throw off this anarchy was going to knock out a country that preferred Triumph of the Will.David Thomson

6. Dr Strangelove

We may think of 1964 as the year the Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show or as the last year of peace before America set itself to annihilating in earnest the small Republic of North Vietnam, but it was also the year Khrushchev was overthrown and China detonated its own atomic bomb (weirdly, those two things happened on the same day). In the aftermath of the Kennedy assassination, these were things that seemed worth being terrified of.

Thankfully, Stanley Kubrick, Terry Southern and Peter Sellers were on hand to make us feel better about the end of the world as we knew it, and about the psychopathic childishness of our military betters. There had been nothing in comedy like Dr Strangelove ever before. All the gods before whom the America of the stolid, paranoid 50s had genuflected – the Bomb, the Pentagon, the National Security State, the president himself, Texan masculinity and the alleged Commie menace of water-fluoridation – went into the wood-chipper and never got the same respect ever again.

Southern, in particular, was wise to the nonsensical macho posturing of the US military-industrial complex, and had no time whatsoever for the uniformed ignoramuses pontificating about mutually assured destruction, fail-safe trajectories and world targets in megadeaths (as one top-secret file is named). Thus he makes General Jack Ripper (Sterling Hayden) a barmy, paranoid repository for every last idiocy the military was spitting out at each new press conference on Vietnam or nuclear-attack policies.

And if you think General Ripper is an over-the-top slur on the good name of America's military might, then you've never come across the real-life head of strategic air command, US Air Force General Curtis "Bombs Away" LeMay – as floridly insane as any character in Strangelove.

No wonder the audiences' initial reaction was one of horror that these verities should be questioned, or such figures ridiculed. Once they got over that, they never stopped laughing, and one small, important cornerstone of the nation's respect for the military was smartly tugged out, leaving the destruction of the edifice itself to the war planners. They would tear it down without the aid of satire before the decade was out. A comic masterpiece that's also deeply serious and perceptive about the mad military mindset of those times, Dr Strangelove's genius endures even as we bury the weapons we once feared so much. John Patterson

5. The Ladykillers

The Ladykillers was the last of the great Ealing comedies and, almost by default, the dying gasp of a vanishing London; still rationed and rubble-strewn, with steam trains on the tracks and carthorses on the streets.

Shot in 1955 by Alexander Mackendrick, from a script that purportedly came to writer William Rose in a dream, this film charts the misadventures of a gang of thieves who hole up in the home of a guileless widow. Mrs Wilberforce (Katie Johnson) lives in a lopsided house up a King's Cross cul-de-sac, a place that rings to the din of steam whistles and parrot squawks. It becomes the base for a bullion robbery hatched by the oily Professor Marcus (Alec Guinness), who convinces the owner that he and his associates (Peter Sellers and Herbert Lom among them) are actually members of a string quartet. The musicians need a rehearsal space and Mrs Wilberforce is only to happy to oblige, standing on the landing and thrilling to the strains of Boccherini's Minuet (Third Movement) as played on an antique turntable. "You liked that, huh?" mumbles the brutish One Round (Danny Green), who wouldn't know a cello from a hole in the ground.

How does one improve on a film as brisk, pungent and bracing as this? The Coen brothers notoriously tried and failed with their fumbled 2004 remake – a film that seemed to miss (or at least misread) all the elements that made the original so special. "It's an Ealing comedy so there's something very British and genteel about it," Joel Coen sniffed at the time. "That isn't particularly our thing." Genteel? What film was he watching, exactly? The Ladykillers is as black as pitch and as corrosive as battery acid. The crims are picked off one by one; victims of their greed and wickedness while their supposed target bobs – vaguely, innocently – just out of reach.

God, it seems, protects drunks, little children and meddlesome old women with too much time on their hands. So hang on to your handbag and keep the parrot in its cage. Once darkness falls and the goods trains start rolling, this dream of a film can feel suspiciously like a nightmare. Xan Brooks

4. Team America: World Police

Released a year into the Iraq war, this was the first and perhaps the funniest of Hollywood's early reactions to the messy conflict. Based on a brilliantly simple and idiotic conceit – an action movie with puppets, in the style of Gerry "Thunderbirds" Anderson's "supermarionation" – it turns the same scatological splatter-gun on America's jumped-up sense of itself as policeman to the planet that writer-directors Trey Parker and Matt Stone had used on TV in South Park.

Thus our heroes are idiots to their core who spout mindless security-state boilerplate or burst into such patriotic songs as America, Fuck Yeah! In the majestically over-the-top opening sequence, they manage to defeat the terrorists, but at the expense of knocking over the Eiffel Tower (on to the Arc de Triomphe and the Louvre), thus earning the enmity of the French for all time (like they didn't already have that).

Soon Team America is at war with a leftie coalition called the Film Actors' Guild (oh yes, FAG), comprised of celebrities all voiced by Stone and Parker, with Michael Moore, Alec Baldwin, Matt Damon and Sean Penn taking an epic amount of crap for their troubles. Kim Jong-il also makes a major appearance, singing I'm So Ronery in typical South Park "is-it-racist?" style.

Predictably there were censorship problems, given the almost nauseating amounts of scatology and violence. The film-makers described their tribulations with the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) at length in Kirby Dick's anti-censorship documentary, This Film Is Not Yet Rated, and many of the excised scenes made it on to the DVD release. Three cheers for bonus features! JP

3. Some Like It Hot

Though it takes place in the Roaring Twenties, Some Like it Hot can be thought of as the first great American comedy of the swinging 60s. It was so advanced for its time in its sexual mores that it won the double-standard for offensive Hollywood cultural product: it was released without the Motion Picture Association of America's seal of approval, and very much with a C (condemned) rating from the Catholic Church's Legion of Decency.

Luckily for director Billy Wilder, who'd made a career of cocking snooks at the censors and the bluenoses, audiences were beginning now to care less and less for the restrictions peddled by the MPAA and the Legion. Wilder was one of the directors (along with Otto Preminger) who helped Hollywood cinema finally grow up. For this we thank him.

And he did it with transvestites. Dressing up Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon as showband strumpets on the run from the Chicago mob, on their way to Miami with Sweet Sue's Society Syncopators (lead singer and signature bombshell: one Marilyn Monroe), allowed Wilder and his co-writer IAL Diamond to run every variation on sexual partnerships, homoerotic confusion and misalliance, and the war between the sexes. There are moments in it that still look fresh and ahead of its (and even our) times, the final line "Nobody's perfect!" being one such moment.

So it's a wonder that this sprightly, evergreen comedy was made under such arduous circumstances, largely thanks to Monroe as her off-street life rapidly fell apart around her. Curtis claims he never said working with Marilyn was "like kissing Hitler", but we print the legend anyway – because it's more fun. Despite the back story, Monroe was never more mind-bendingly pneumatic or winningly beautiful than she was here. A perfect American comedy. JP

2. Borat

Could anyone have foreseen just how great a comedy Borat – or to give it its full title, Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan – was going to be? Its star, Sacha Baron Cohen, had honed the satirical stunt documentary to perfection in his Ali G TV series, but had crashed and burned when trying to put the character on the big screen, in the awful Ali G Indahouse. It's still a bit of a mystery why Baron Cohen ever got the chance to make a follow-up, but he wisely went back to the format that had proved itself time and again on TV: set up an apparently clueless fictional character, and send him in to encounter real-life types and get them to make idiots of themselves. Borat, the cheerfully antisemitic TV presenter from Kazakhstan, who had populated Baron Cohen's TV spots since the late 90s, may not have appeared promising material for a feature, but boy, was everyone wrong.

The film is based on a simple idea: Borat is making a documentary about the US. But the opening section, in which he introduces his home village and its inhabitants, establishes a tone of breathtaking offensiveness. The "Kazakh" actors clearly have no idea about the outrageous things Borat is saying about them, and Baron Cohen crowns proceedings by staging a "running of the Jew", supposedly a regular local pastime. Thus the stage is set: the film is an incredibly cruel satire, aimed at both post-Soviet bigotry and American social dysfunction.

By the time he gets to the US, Baron Cohen is in full flow, the superficial ingenuousness of his creation opening all sorts of doors. Arguably the most spectacular, and certainly unplanned, result is the consternation he causes by bravely singing a spoof national anthem at a rodeo in Texas; the electric hostility he triggers in the spectators unnerves one of the horses so much it stumbles and falls to the ground.

Baron Cohen, as has been pointed out, can be faulted perhaps for bamboozling the uncomprehending and the weak. But that misses the point of much of what makes Borat great: the joke is almost always on him as well. The sort of comedy that Baron Cohen is trying for is high-risk for sure, and hardly guaranteed to provide results – but Borat is all gold. We may never see its like again. Andrew Pulver

1. Annie Hall

Woody Allen's nakedly autobiographical film is the Oscar-winning sensation which put him on the map – and it's probably his best film, too. This fictionalised account of the rise and fall of a "nervous romance" between Jewish New York comic Alvy Singer (Allen) and the willowy, Waspy Annie Hall (Diane Keaton) was the high-water mark of Allen's gift for sublimely touching and funny screen comedy. It is a gloriously convincing romance, packed with superb gags. Annie Hall also virtually invented the relationship comedy in both movies and literature; it made possible the now degraded romcom genre, and on TV it spawned Seinfeld, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Sex and the City, and Entourage – though none of these have anything like Annie Hall's passionate romantic pain.

It is an ancestor of the work of Charlie Kaufman, which comes closer to Allen's own darkness. Throwaway jokes about Alvy's paranoid encounters with his TV-watching public look very contemporary in our celeb-happy age. The sensationally funny and daring cameo for Marshall McLuhan, who magically appears in a cinema queue to tell some loudmouth academic that he is wrong and Alvy is right, is an inspired and sophisticated flourish. It depended on a literate audience, who would also be tickled by the idea of a Henry James novel called My Sexual Problem. The film's concluding device – the ecstatic montage of his lost relationship's most poignantly magical memories – incidentally lives on in the Big-Brother-reality-TV convention of showing the departed competitor his or her best moments in the house.

The fact that the movie was originally to be entitled Anhedonia, that is, the clinical inability to experience happiness, has become part of its legend, especially because the film has given everyone so much happiness. It was, in fact, the movie which introduced us most fully to Allen's very serious obsession with death: how fleeting life is, how dependent on chance, and how overshadowed it is by the thought of its approaching end. Life is negligible and horrible, like the food in a restaurant in the Catskills-type joke Alvy tells at the very beginning: terrible, and such small portions. But in Annie Hall the mortality that weighs most heavily is the mortality of his love affair. There are no wedding bells or happy endings, and that is what gives the movie its sting. Allen also captured something in Keaton which can't be described except in cliches: kookiness, wackiness, ditsiness. They have a sexual relationship, and yet Keaton is not portrayed in a very sexualised way: she looks beautiful, but shambolically real.

The question at the heart of the film is: what went wrong? How did the romance die? Alvy introduces his story as an autopsy, a re-examination of his life and behaviour, and a doomed attempt to find out why his relationship with Annie failed. There is no answer: just a deeply touching, funny, brilliantly told story.

When I first saw the film, I remember being stunned with Allen's sheer audacity in the scene where he remembers his old schoolroom, sitting alongside kids who harangue him in adult language about his sexual precocity: "For God's sake, Alvy, even Freud speaks of a latency period!" One extraordinary girl in glasses addresses the camera and says: "I'm into leather." I've never been able to watch Annie Hall without pondering the fact that this child is now an adult. Where is she now?

Alvy Singer, like Woody Allen, tries writing scenes based on his own life: to make sense of them, to lessen the pain, to understand what happened, and still the truth eludes him. This wonderfully funny, unbearably sad film is a miracle of comic writing and inspired film-making. Peter Bradshaw

SOURCE: http://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2013/oct/11/top-10-comedy-movies

No comments:

Post a Comment